So, if you’re reading this you most likely know that I’m a first-year medical school student in the US. And a month or so ago, we learned a common physical diagnosis technique—a funky one called “tactile fremitus.” Now, this isn’t one I’ve actually had done to me by a doctor, and it’s probably not one you’ve had done to you by a doctor, but it’s commonly taught in medical schools anyway.

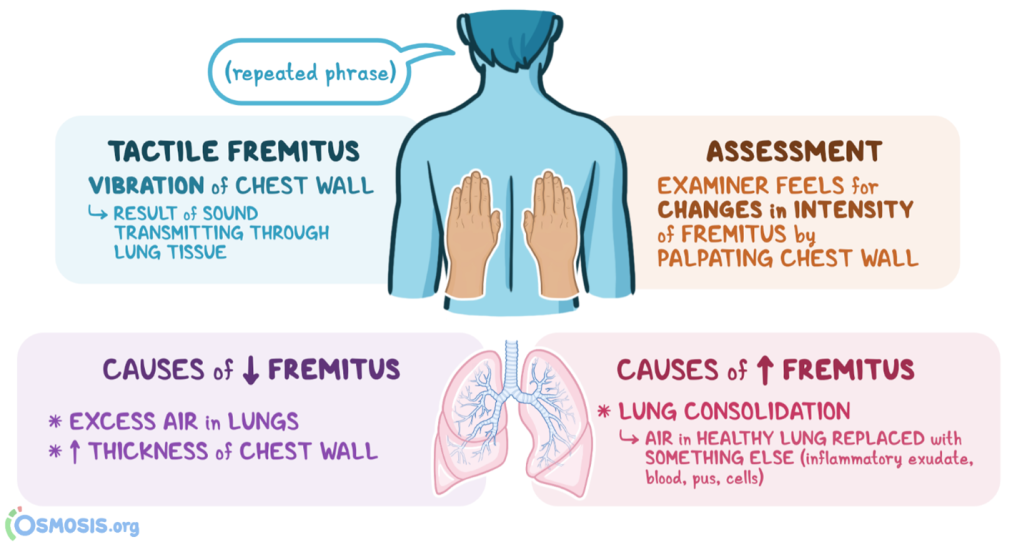

Before we dig into the interesting stuff, here are the basics of tactile fremitus. It’s used as part of a pulmonary exam to see if there is air or fluid in your lungs. The doctor places the blades of their hands along your chest wall and asks you to repeat a phrase. As you speak, vibrations travel from your vocal cords through the lung tissue to the chest wall, where they can then be felt by a doctor’s hands. If you’ve got excessive air in the lungs, vibrations are usually depressed. Conversely, if you’ve got fluid in there (like with pneumonia), vibrations are usually increased. In a normal person, the “vocal fremitus” should be felt equally on both sides.

Anyhow, when we learned tactile fremitus, the phrase we were told patients should repeat is “ninety-nine.” So, picture in your head one person sitting down, back partially exposed, and another person in a white coat standing behind them, hands on their back, asking them to repeat “ninety-nine” several times. That’s what a tactile fremitus test looks like. Fun, right?

Naturally, I wondered, why “ninety-nine”? Why not, you know “one hundred”? Or something else entirely?

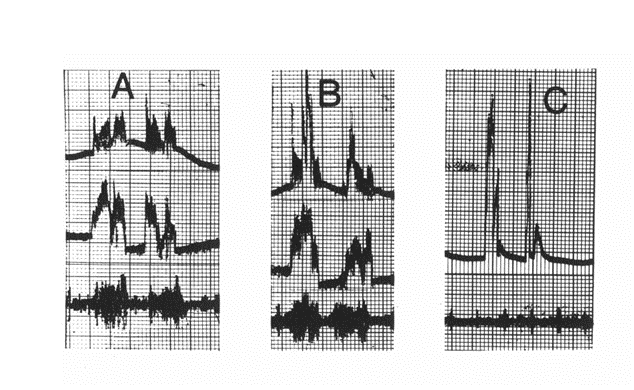

It turns out that I was not the only one wondering such a thing. In 1973, Dr. William Dock published a study in the Bulletin of the NY Academy of Medicine where he rigorously tested the use of ninety-nine. First, you need to understand that the ideal sounds for this test are low frequency ones, as they transmit more effectively through the lung tissue and onto a doctor’s hands. In English, diphthongs (two vowel sounds smushed together) will do the job. So, Dr. Dock strapped mics to volunteers’ chests and recorded them saying “ninety-nine” as well as a few other choice phrases—“boy boy” and “boogie woogie” (it was the seventies, I guess). It turns out that “ninety-nine” was not a good word to use for tactile fremitus at all.

Here’s Dr. Dock’s graph. A represents “boogie woogie,” B represents “boy boy,” and C represents “ninety-nine.” The top lines are sounds above 240 Hz, the middle lines sounds between 80 and 240 Hz, and the bottom lines sounds 20-80 Hz. (C only shows the top and bottom lines). As you can see, “boogie woogie” and “boy boy” produce far more low frequency sounds compared with “ninety-nine.”

Why is everyone taught “ninety-nine” then? According to Dr. Dock, when physicians from the US were visiting Austria and Germany, they saw tactile fremitus being used with the phrase neun und neunzig—ninety-nine in German. That worked for them, since ninety-nine in German had a deep, low-frequency-producing “oy” sound. But in English, no dice. A classic case of direct, literal translation that didn’t have the intended practical use. And apparently, no one bothered to question it. Forty-eight years later from Dr. Dock’s revelation, we’re still being taught the bum number rather than the much more juicy “boogie woogie.”

In 2016, Anna Harris, an Associate Professor at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, addressed this lag in an article for the Journal of Graduate Medical Education. Harris mentioned that in the Netherlands (where students are taught mostly in Dutch), some schools hopped eleven digits down to eighty-eight, or achtentachtig, to get the adequate tremors. Even then though, certain accents made the word too soft, and so Amsterdam was suggested. Why do we keep using ninety-nine? According to Harris, “because 99 is a habit, ingrained in the ritual of physical examination”—and rituals are important.

It’s not just tactile fremitus and ninety-nine. Digging into Dr. Dock’s article further made me think about the other ways we use sound in medicine, a focus of Prof. Harris’ own research. For instance, how do we communicate what certain sounds sound like? Such questions are not only intellectually intriguing, but also medically important. According to Dr. Dock, physicians used all sorts of methods to get across the sounds emanating from their patient’s insides, often heard via stethoscope (aka auscultation). “Sounds of sea gulls crying, cranes whooping, geese honking, and horses clattering down dirt roads were once fine analogues for certain cardiac murmurs or sonic rhythms,” Dock wrote. In fact, Dock reports, some docs even mimicked heart sounds by using the hems of their white coats as a kind of guitar string, holding it at different lengths and plucking it to simulate clicks and taps from valves and vessels.

We all know the heart goes “lub dub,” right? According to Dr. Dock, wrong. Unsatisfied with tearing apart just tactile fremitus, he compared recordings of people saying the words “lub dub” with actual heart sounds. Turns out, “lub dub” doesn’t do a good job either. A better fit might be “click click.”

Of course, the evidence for all this is weak, at best. Dr. Dock doesn’t seem to have repeated his tests all that many times, and his method of strapping a mic to a person’s chest might not be the most accurate. But his ragtag endeavors at questioning the status quo are inspiring. What else could physicians be listening for, and how could they do it better? As I’ve seen in just a few months of medical school, sound is essential to understanding and examining the human body. From lung sounds to heart sounds to bowel sounds, we make all sorts of noises—and subtle variations in those noises could mean the difference between healthy and sick.

And how do we teach the art of listening to students? And how do we, as students, learn? The first heart sound I truly listened to was that of my instructor—who happened to have a heart murmur (she was born with it, and she was fine). As I placed my stethoscope over her chest and focused closely, I heard two thumps, with a whoosh in between. Was what I heard the right thing? How could I describe what I was hearing, and compare it with what I was supposed to have heard? I had never really considered how important it was to have the right language to convey a deeply felt sensation like sound.

I’ll get off my soapbox now, but this is a topic I want to keep digging into. I’ve read a lot about the “death of the physical exam” and how telemedicine might be changing doctor’s visits, and I wonder how that will change the use of senses like sound. Professor Anna Harris, of Maastricht, seems to be doing a lot of work on this—and I mention this because I reached out to her for an interview for this piece. She was understandably busy, but if I ever get a hold of her (Dr. Harris, I would still love to speak with you, even briefly!) or one of her collaborators, you can be sure I’ll have a follow-up post with more on this. Till then, I’ll leave you with a wonderful couplet Dr. Dock himself composed:

Lub dub does not the heart sounds fake

Nor ninety-nine the thorax shake.